Pros and Cons of Daycare for Infants Peer Reviews

In 1997, when Quebec, Canada, launched total-twenty-four hour period, year-round child care for all children nether historic period 5, the title of its policy brief read, "Children at the center of our pick." The assumption, of course, was that government-subsidized, universal 24-hour interval care would provide all children the potential for a "healthy start" in life, while simultaneously enabling many more than women to enter the workforce and increase their earning potential.

Within x years, comprehensive analyses of the universal, "$5 per 24-hour interval childcare" plan, including its impact on child intendance employ, employment patterns, and children'south and parent outcomes, suggested cause for business organization. Social development among children, equally indicated past both emotional and behavioral measures, had significantly deteriorated in Quebec, relative to the rest of Canada (10% of a standard deviation lower). Comparisons between children ages 2 to 4 who had been exposed to the program, with older children (and siblings) who had not, revealed significant increases in feet, hyperactivity, and aggression in those exposed to the plan. And the analyses establish more hostile, inconsistent parenting, and lower-quality parental relationships among parents of children exposed to the programme. But it was hard to predict whether the negative outcomes identified for two- to 4-twelvemonth-olds would persist across their development, or simply dissipate.

For decades, early intervention programs for children from high-risk environments, such every bit Caput Offset, the Perry Preschool Project, and the Abecedarian Projection, had explored whether intensive positive intervention in a child's early on years really carried through to machismo past improving economic outcomes and lowering incidence of criminal behavior. Evidence suggested that some of these positive effects did persist in adulthood. Merely would the aforementioned be true of negativeoutcomes associated with exposure to programs in early childhood?

Twenty years afterwards the Quebec program's implementation, a second prepare of comprehensive analyses were conducted by Michael Baker, Jonathan Gruber, and Kevin Milligan (forthcoming, in the American Economic Journal). After replicating the previous results for children ages 0 to 4, the authors explored whether the negative outcomes associated with exposure to Quebec's early, extensive mean solar day care program persisted into ages v to 9, the pre-teen years, adolescence, and young machismo.

Their research confirmed that the negative effects did proceed, and in some cases became stronger beyond development. Among five to 9-year-olds, negative social-emotional outcomes not only persisted, but in some cases increased, as indicated past 24% of a standard departure increment in anxiety, a 19% increment in aggression, and a xiii% in hyperactivity. The impact on boys and children with the most elevated behavioral problems was stronger, especially in measures of hyperactivity and aggression.

Using a specific type of regression analyses based on what is called "The Recentered Influence Function" (RIF), Baker, Gruber, and Milligan institute that the "primary impact" of the Quebec program was to increase behavioral issues specially "for those who already had high scores."

Source: M. Bakery, J. Gruber, & Thousand. Milligan, "The Long-Run Impacts of a Universal Child Care Program," eleven/8/eighteen

Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of theAmerican Economical Journal: Economical Policy.

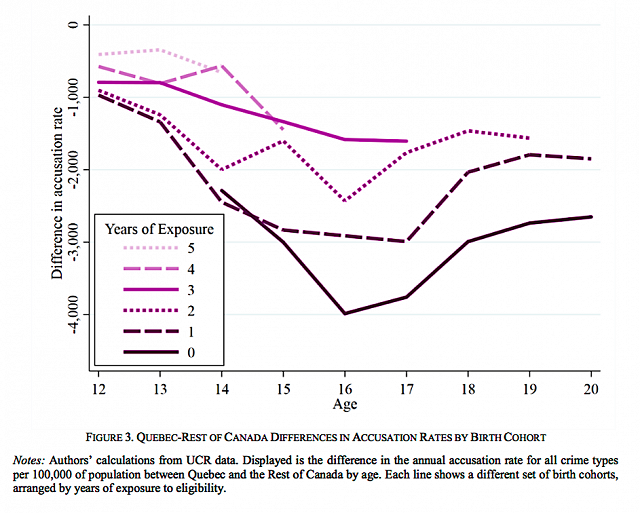

For youth and young adults, ages 12 to 20, analyses of cocky-reported general health and life satisfaction indicated that negative social-emotional outcomes associated with exposure to the daycare program persisted into immature machismo. The almost striking finding was a "sharp and contemporaneous increase in criminal behavior" for those exposed to the universal day intendance program compared to their peers in other provinces. Though crime rates in Quebec are lower than the rest of Canada, there was a significant increment in crime accusation and conviction rates for those cohorts exposed to the Quebec child care program. There was an increase of 19% in the average rate of criminal accusations and an increase of 22% in the boilerplate rate of criminal convictions. As with the v- to 9-year-old measures, the impact on criminal behavior was greater for boys, and for those who already had elevated behavioral problems.

Source: M. Baker, J. Gruber, & K. Milligan, "The Long-Run Impacts of a Universal Child Care Programme," 11/8/xviii

Copyright American Economic Clan; reproduced with permission of theAmerican Economic Journal: Economic Policy

Bakery, Gruber, and Milligan acknowledge that there is some evidence of positive impacts from universal child care programs in certain nations for children of certain ages. But in most cases, the benefits are primarily for less-advantaged children. Equally they conclude, "There is little articulate show that these programs provide meaning benefits more than broadly."

The timing and extent of the Quebec child care programme provided the unique opportunity to comprehensively evaluate the implications of a universal twenty-four hours intendance program on many children from childhood to young adulthood. Importantly, the findings from the Quebec programme are largely consistent with findings from the National Plant of Child Health and Human Development's comprehensive evaluation of day care in the U.s.. That written report, which followed the same 1,364 children every yr from birth, constitute that extensive hours in solar day intendance early on in life predicted negative behavioral outcomes throughout development, including in the final assessments washed when the children were 15 years old.

By historic period iv-and-a-half, extensive hours in day care predicted negative social outcomes in every area including social competence, externalizing problems, and adult-kid disharmonize, generally at a rate three times higher than other children. In caregiver reports of behavioral issues, only 2% of children who averaged less than ten hours per calendar week of day care during the first 4 years of life had at-risk scores, while as much as 18% of children who averaged more than than 30 hours per calendar week did. Family economic status, maternal pedagogy, quality of child care, and caregiver closeness did not moderate these effects. Just would those effects persist?

Past third course, children who had experienced more hours of non-maternal care were rated by teachers as having fewer social skills and poorer work habits. More time in 24-hour interval care centers specifically predicted more externalizing behaviors and instructor conflict, also. Hours spent in day intendance centers specifically continued to predict problem behaviors into sixth grade. But by age 15, extensive hours before age four-an-a-half in any type of "nonrelative" care predicted problem behaviors, including chance-taking behaviors such equally alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, stealing or harming belongings, likewise as impulsivity in participating in unsafe activities, fifty-fifty after decision-making for 24-hour interval intendance quality, socioeconomic background, and parenting quality. And much similar the findings for the Quebec childcare program, the statistical effects linking day care hours with problem behaviors at historic period four-and-a-one-half were nearly the aforementioned as the statistical furnishings at age 15.

Equally with the persistence of negative effects beyond evolution, there is too evidence for the persistence of positive effects when children are exposed to the highest quality daycare. Higher developed-kid ratios and more sensitive and positive caregiving in day care have consistently been associated with better cognitive performance and fewer behavioral issues in children. Some of those positive effects announced to be lasting. Findings from the NICHD-SECC plant that higher quality child care was associated with a significant increase in cognitive-academic achievement scores at age 15 for children who experienced the highest levels of quality. And later research evaluating a subsample of these students institute that the highest quality child intendance predicted higher grades and admission to more selective colleges afterward loftier school graduation. The effects were small simply consistent beyond the outcomes from kindergarten through 12thgrade, confirming that the positive effects of high-quality child care can persist beyond development.

But, every bit enquiry on the Quebec plan found, the highest level of quality tin can be hard to secure. In 2005, 60% of the universal solar day intendance program sites in Quebec were judged to be of "minimal quality." But 1-quarter of the sites provided intendance that met the standards necessary to authorize equally good, very expert, or excellent. Such findings are comparable to many other developed countries, confirming just how challenging it is for children to have access to the quality of care necessary for persistent positive gains over the long run. And these small-scale gains have to exist weighed against the risks of spending extensive hours in twenty-four hour period care. The comprehensive evaluation of twenty-four hours care quality done in the NICHD-SECC found that extensive hours in 24-hour interval care early on in life predicted negative behavioral outcomes throughout childhood and in to adolescence, even after controlling for day care quality, socioeconomic background, and parenting quality.

If our children are "at the heart of our choice," then the inquiry confirming that children exposed to early, all-encompassing day care are at run a risk for social-emotional and behavioral challenges must be taken seriously. In the last decade, more sophisticated analytical methods have allowed social scientists to place "pour effects" showing how social behavioral challenges in early on life predict challenges with bookish competence in adolescence, which then predicts other social-emotional challenges in young adulthood. Other research identifying "cascade effects," found that lower academic competence at ages iv to 5 predicted social-emotional bug at ages six to seven, which then predicted social-behavioral problems at ages 12 to 13, followed by greater depression at historic period 16.

Clearly, more enquiry is needed to understand the implications of extensive hours of day care in early on life beyond development and into young machismo. What nosotros do know suggests that all-encompassing time spent in not-maternal care in early life has effects that persist beyond the entire course of development. Though the effects may appear minor, they matter in the lives of individual children, and they matter in the collective consequences to communities and society at big.

Jenet Erickson is an affiliated scholar of the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University.

Source: https://ifstudies.org/blog/measuring-the-long-term-effects-of-early-extensive-day-care

Post a Comment for "Pros and Cons of Daycare for Infants Peer Reviews"